Endoscopy Essentials: Lower Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Series. Part 1: Overview of Lower Gastrointestinal Endoscopy

As originally published in Today's Veterinary Practice," July/August 2016 (Volume 6, Number 4)

Patrick S. Moyle, DVM, and Alex Gallagher, DVM, MS, Diplomate ACVIM

University of Florida

Welcome to Endoscopy Essentials, a column that discusses endoscopic evaluation of specific body systems, reviewing indications, disease abnormalities, and proper endoscopic techniques. Visit tvpjournal.com to read the first three Endoscopy Essentials articles:

- Overview of Upper Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (November/December 2014)

- Upper Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Techniques (March/April 2015)

- Endoscopic Foreign Body Retrieval (November/December 2015).

Lower gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy is a minimally invasive diagnostic technique that allows the clinician to evaluate the mucosal surfaces of the rectum, colon, ileocolic sphincter, cecum, and distal small intestine (ileum) (Figure 1). Lower GI endoscopy can be used:

- Diagnostically, to collect biopsy samples in animals with chronic large bowel disease (colonoscopy) and/or chronic small bowel disease (ileoscopy)

- Therapeutically, for treatment of strictures, foreign bodies, polyps, and tumors.

COLONOSCOPY & PROCTOSCOPY

Indications

Colonoscopy and proctoscopy have similar indications—both are important diagnostic modalities for evaluating animals with clinical signs referable to the large bowel. These signs may include diarrhea with increased frequency, tenesmus, dyschezia, hematochezia, increased fecal mucus, and occasionally, constipation/obstipation (Table 1).

Many animals with large bowel disease can be diagnosed and/or treated by less invasive options and do not require colonoscopy. Hence, a rational, stepwise diagnostic and therapeutic plan should be pursued before colonoscopy or proctoscopy is performed.

Differences in proctoscopy and colonoscopy technique will be addressed in Part 2 of this article series.

Evaluation Prior to Endoscopy

Digital rectal examination should be performed to evaluate for rectal masses, strictures, and mucosal abnormalities. Recommended diagnostics for animals undergoing lower GI endoscopy are listed in Table 2.

FIGURE 2. Whipworms in the ascending colon of a dog. Appropriate deworming is recommended prior to endoscopy.

Therapeutics Prior to Endoscopy

Recommended therapeutics for animals undergoing lower GI endoscopy are listed in Table 3. If the aforementioned diagnostics and empiric therapies fail to improve the patient, biopsy is recommended before immunosuppressive therapy is initiated.

Intestinal dysbiosis relates to alterations in the microbiota throughout the small and large intestines, while GI dysbiosis refers to microbiota abnormalities anywhere along the GI tract.

During Endoscopy: Normal Appearance

Colon

The normal appearance of the colonic mucosa is smooth, pale pink, and glistening (Figure 3). Submucosal blood vessels should be readily apparent throughout the length of the colon. Lack of visualization of the submucosal vessels suggests mucosal thickening secondary to edema or infiltrative diseases.

FIGURE 3. Normal appearance of the descending colon in a dog. The mucosal surface is smooth, light pink, and glistening. The submucosal blood vessels are easily visible.

Occasional lymphoid follicles can be observed in the normal colon of dogs and cats. A variable amount of adhered fecal material may be visualized depending on the quality of the patient preparation.

Mucosal hyperemia should be interpreted cautiously. Hyperemia can be a normal physiologic response to warm water enemas or mild trauma from the endoscope but can also be due to inflammatory disease.

Ileocolic & Cecocolic Junctions

At the most orad portion of the ascending colon, both the ileocolic and cecocolic junctions are visualized. The cecocolic sphincter is often open or partially open and usually can be entered.

Cecum

The mucosa of the cecum is smooth and pale pink, with submucosal blood vessels readily visible. In the dog, the cecum is a spiral structure that can be up to 30 cm in length and terminates in a blind end. In the cat, the cecum is extremely short, and the entirety of the structure can usually be examined from the ascending colon.

During Endoscopy: Colonic Abnormalities

Inflammatory Bowel Disease

The appearance of inflammatory colitis ranges from normal to severe mucosal changes. Frequently, the mucosa will appear focally to diffusely hyperemic, irregular, or granular. In more severe cases, ulceration or erosions may be present. Areas of mucosal hemorrhage may be present as well. The mucosa may be friable as the scope is advanced. Frequently, submucosal blood vessels are not visible (Figures 4 and 5).

FIGURE 4. Ascending colon in a dog with mild lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory bowel disease. The mucosal surface is mildly hyperemic, and submucosal blood vessels are not readily visible. The ileocolic sphincter is closed and the cecocolic sphincter is open, enabling visualization of the proximal cecum.

FIGURE 5. Descending colon in a dog with lymphoplasmacytic and eosinophilic colitis. The mucosal surface has a cobblestone appearance and contains multifocal areas of mucosal hemorrhage. Submucosal blood vessels are not visualized.

Histiocytic Ulcerative Colitis

In dogs with histiocytic ulcerative colitis, the colonic mucosa may contain multifocal areas of ulceration and erosion, often with mild to marked intraluminal hemorrhage, depending on the chronicity of the disease. In areas that lack ulceration, the submucosal blood vessels are frequently not seen.

Infiltrative Infectious Organisms

The endoscopic appearance of infiltrative infectious diseases (pythiosis, protothecosis, and histoplasmosis) cannot be distinguished from that of inflammatory bowel disease. The colonic mucosa may appear normal, discolored, or granular with multifocal areas of ulceration. Occasionally, the lesions may appear more nodular or mass-like. The mucosa can be friable, and submucosal blood vessels are rarely seen.

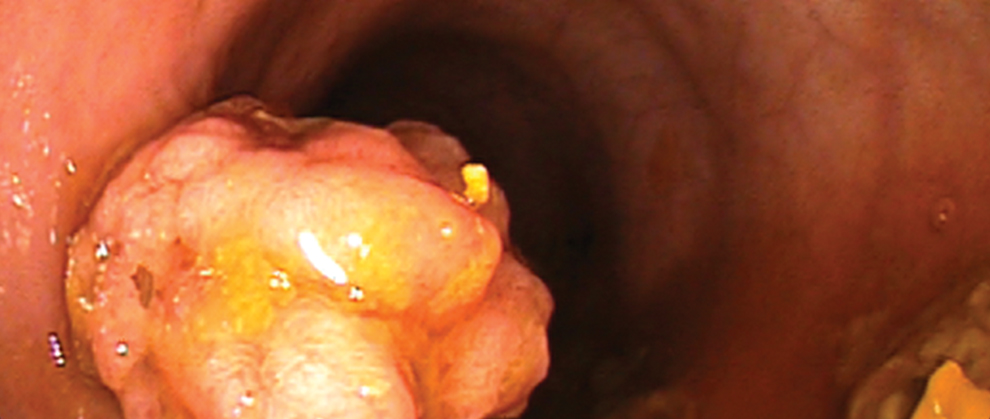

Adenomatous Polyps

When present, benign polyps are mucosal lesions seen in the colon or rectum of dogs (Figure 6). Often, only a solitary mass is encountered, but multiple lesions can be seen. The masses are broad-based or pedunculated and can have a smooth or irregular surface. The remainder of the colonic mucosa usually appears normal.

Neoplasia

Colonic neoplasia has a wide variety of appearances. It can occur as generalized infiltrative disease or a solitary mass.

Adenocarcinoma, the most common neoplasia in the colon of dogs and cats, often occurs in the rectum or descending colon but may be anywhere in the large bowel (Figure 7). If a discrete mass is present, it can appear nodular, pedunculated, broad-based, or polypoid. Alternatively, adenocarcinoma can appear as a circumferential narrowing of the lumen. The surface of the lesion often contains ulcers or erosions, is easily friable, and can have a variable amount of associated hemorrhage.

FIGURE 7. Descending colon in a dog with an annular adenocarcinoma. The surface of the mass is irregular and contains multifocal pinpoint areas of hemorrhage.

Lymphoma can also have a wide variety of appearances. Lymphoma can be indistinguishable from inflammatory bowel disease or may appear as diffuse nodular thickening, a broad-based mass, or segmental circumferential narrowing of the colonic lumen. The mucosa can contain ulcerations or erosions and may be friable.

ILEOSCOPY

Indications

Ileoscopy should be considered in any animal with chronic or recurrent clinical signs referable to the small intestines. Clinical signs associated with small intestinal disease include vomiting, weight loss, and small bowel diarrhea (Table 1). Recent studies suggest that biopsy of the ileum increases the diagnostic yield of endoscopic sampling (Figure 8).

FIGURE 8. Ileum of a dog with moderate lymphoplasmacytic inflammatory bowel disease. The ileal mucosa is pale in appearance and has a markedly irregular and granular appearance.

In addition, in some patients, ileoscopy is performed as an extension of colonoscopy because severe distal small intestinal disease can present with large intestinal signs.

As is the case with colonoscopy, many animals with small bowel disease do not require endoscopy, and animals should undergo a full diagnostic workup and empiric therapy before endoscopy.

Evaluation Prior to Endoscopy

Recommended diagnostics (Table 2) for animals prior to ileoscopy are identical to those for animals undergoing upper GI endoscopy.

Therapeutics Prior to Endoscopy

After a thorough diagnostic evaluation, empiric therapies are typically recommended (Table 3), unless the clinical condition of the animal (eg, complete anorexia, severe weight loss, or hypoalbuminemia) dictates further evaluation immediately.

During Endoscopy: Normal Appearance

Ileocolic & Cecocolic Sphincters

In dogs, the ileocolic sphincter normally appears as a smooth mucosal cuff of tissue. In cats, the ileocolic sphincter can appear as a smaller mucosal cuff or a mucosal fold. In either species, the cecocolic junction is generally visualized immediately adjacent to the ileocolic sphincter.

Ileum

The opening to the ileum is located in the center of the ileocolic junction. The normal ileal mucosa is similar to that of the duodenum and is light pink with a velvet-like texture. In contrast to the proximal small intestines, Peyer’s patches are present in high concentrations in the terminal ileum.

During Endoscopy: Colonic Abnormalities

Because ileoscopy is an extension of upper GI endoscopy, small intestinal lesions visualized by endoscopy are described in the Upper Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Series; see Part 1: Overview of Upper Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (November/December 2014) and Part 2: Upper Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Techniques(March/April 2015), available at tvpjournal.com.

IN SUMMARY

Lower GI endoscopy is a minimally invasive diagnostic technique to evaluate the rectum, colon, cecum, and ileum and obtain biopsy samples in animals with chronic small and large bowel disease. All animals with chronic GI signs should undergo an appropriate diagnostic evaluation and therapeutic trials before endoscopy because many patients do not require this procedure.

Part 2 of this article series will outline preparation and techniques for performing lower GI endoscopy.

GI = gastrointestinal

Patrick S. Moyle, DVM, is a second-year resident in small animal internal medicine at University of Florida College of Veterinary Medicine. He received his DVM from Auburn University and completed an internship at Wheat Ridge Animal Hospital in Wheat Ridge, Colorado.

Alex Gallagher, DVM, MS, Diplomate ACVIM, is a clinical assistant professor of small animal medicine at University of Florida College of Veterinary Medicine, where he also received his DVM. He completed a rotating internship at Virginia–Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine; an internal medicine internship at Affiliated Veterinary Specialists in Maitland, Florida; and a residency in internal medicine at Virginia–Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine.